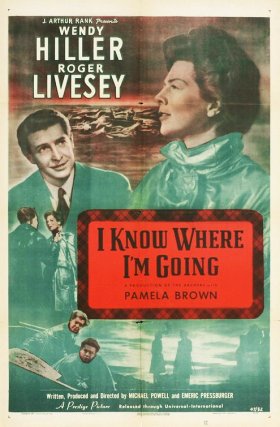

A Conservative Obligation: Michael Powell’s “I Know Where I’m Going” (1945)

From the desk of Thomas F. Bertonneau on Tue, 2009-12-22 07:15

In respect of The Adventures of Robin Hood, I have remarked in an article [here], for MediaHope, how one of the strongest recommending features of Curtiz’s superbly mounted medieval epic is that, at its heart, the film tells a moving conversion story – actually a pair of them, Marian’s and Robin’s, that the screenwriters skillfully intertwine. In the same article I reiterated critic René Girard’s argument that all effective narrative turns on plausible conversion and that reading itself is a type of conversion experience. If Girard’s point were valid for written narrative then why would it not likewise be so for film? Like Curtiz’s Robin Hood, Powell’s I Know Where I’m Going tells a conversion story, brilliantly, and uses it to make a profound filmic critique of the crassness that pervades modern life. I should add that in neither instance is it a case of religious conversion but rather of something subtler.

As Powell’s title suggests, the mainline of his story takes the form of an itinerary. This itinerary begins in industrial Manchester in wartime, in which bustling city the story’s female interest – she is the spoiled daughter of a banker – has succeeded in getting herself engaged to the owner of the factory where she works. She is a typist, viewers surmise, from the pool. From Manchester, the young woman travels to a remote island off Scotland’s northwest coast. Actress Wendy Hiller plays this young woman, Joan Webster, with studious self-absorption. The wealthy industrialist whose bride Joan thinks to become has scheduled the nuptials to occur on insular Kiloran, his summer residence – and, importantly, Joan believes that Sir Robert Bellinger, the prospective groom, is the Laird of Kiloran. Joan’s railway and seaway journey to Mull, the steppingstone island to Kiloran, is not, however, merely a geographical itinerary; it is also a pilgrimage from the flashiness of daddy-subsidized shopping and a nightlife in posh restaurants to the spare “Highlands economy” and tenacious folkways of old Norse-and-Celtic domains.

A Kentshireman born, Powell shot his first auteur film, The Edge of the World (1936), in the Orkneys, where an intact, but acutely threatened, folk-culture provided the social setting. In The Edge of the World, a failure of agriculture on the remote island, the fictional Hirta, leading to the community’s unwilling evacuation to the mainland, compels the islanders into confrontation with modern life. They abandon their old life with great and understandable reluctance. In I Know Where I’m Going, which takes its title from a Scots folksong, Powell reverses the gambit, with Joan, the modern sophisticate, finding herself island-bound, with the necessity of coming to terms with a remnant of medieval society.

Joan’s curriculum vitae in I Know Where I’m Going turns into a prolonged, severe lesson in patience, about which, starting out, she knows precisely nothing. Bad weather strands her on Mull, where her luck precipitates her, much less than willingly, into the thick of local life. She meets in particular Torquil MacNeil, played by Livesey, a Royal Navy officer on eight days’ leave, who, like Joan, wants to reach Kiloran. [View clip here] That Joan and Torquil will fall for one another, every competent filmgoer will foresee: so the drama turns on how, and the how has to do with Joan’s ability to soften her stony heart and gainsay the chattels of spurious social altitude. Joan senses subconsciously, from the moment she meets Torquil, that even the best laid plans of ambitious girls gang aft agley. Primarily then Joan’s struggle is a feisty contest with herself. After Livesey courteously escorts Hiller from Mull’s harbor to the hotel at Tobermorey, away on the other side of the island, she tells him bluntly that she cannot sit down at luncheon with him, and that he knows why.

Livesey’s character – he knows a great deal more about Hiller’s character than she knows about his or about her own – relaxes for the moment into chivalrous, observant non-intervention. “I think you are the most proper young woman I’ve ever met,” says Torquil gently, and a bit sadly, to Joan.

Viewers will grasp that Torquil too, never minding all his propriety, has felt his heart swell. It will have been despite Joan’s glaring egocentrism, and because Torquil can see, far better than Joan, beyond the bratty side of her persona, to a core of decency. Earlier, in a moment of unsolicited disillusionment, Joan has learned directly from Torquil that Bellinger is not the Laird of Kiloran, as she had supposed, but that he, Torquil, is. Matter-of-factly: “I’d better introduce myself. I am MacNeil of Kiloran and I am Laird of Kiloran.” Hiller makes it clear by her wonderful performance that Joan blames Torquil for her error concerning Bellinger’s position. She sends him a dirty look. What a dirty look! Joan’s fantasy about Bellinger, who has allowed her to take him for a laird when he was not one, has nevertheless suffered deflation. Joan’s rapprochement with reality – and with Torquil, and with herself – now stands in the offing. [View clip here]

The middle scenes of the film carefully heighten the contrast between the superciliousness of the city-dwellers, who merely rusticate for a season in “the isles,” while spending money prodigiously, and the laconic generosity and happy frugality of the locals. When I screened I Know Where I’m Going for my students, they had just spent two weeks reading excerpts from Johann Gottfried Herder on the nature of folk-cultures and chapters from two books by the late Neil Postman – Amusing Ourselves to Death and Technopoly – that deal with the great loss of longstanding customs and traditions that characterizes urban existence in the consumer-age. Most modern young people are like Joan. They have no idea of what has been lost by way of custom and tradition, that their great-grandparents knew, sometimes in a foreign language or with an accent, or how valuable that lost lore was. The film illustrates luminously what it means to have a dialect, to know the old songs, to feel rooted in a particular locale, and to be on intimate terms with one’s stubborn neighbors in a community.

In one episode, Torquil rides with Joan, from Tobermorey back to quayside, in the island’s solitary motor coach. When a group of hunters armed with rifles boards the coach midway, all of the men immediately recognize the Laird of Kiloran, as he recognizes them. Bellinger, who merely rents MacNeil’s hereditary fiefdom, “for the duration,” while pretending to status, tells Joan casually by radiophone that none of the locals is “worth knowing.” MacNeil’s attitude to the people inclines by contrast to the democratic, as he asks by name after the relatives of the men. Not knowing Joan for the fiancée, members of the hunting party gossip frankly about “the rich man of Kiloran,” how he orders expensive things sent over from London and how he ignores the beauty and resource of the island.

A particularly jolly fellow registers his dismay satirically by saying, under an arched eyebrow, that Bellinger regularly has filleted salmon brought over from the mainland. When another man inquires incredulously, cannot Bellinger fish for himself, the satirist says, “The rich man of Kiloran – ach – he has the finest tackle from Glasgow, but the fish they do not know him, no.” It is a rapier-like folkloric aperçu, delivered in an amiable burr, which urges forth an amused chuckle from everyone else, except Joan. [View clip here] For the first time in the unfolding story, the viewer actually feels sorry for the stuck-up young woman.

A subplot involves Colonel Barnstaple, played by bigger-than-life character-actor Captain C.W.R. Knight. The Colonel, a keen falconer, proposes to train an eagle – yes, an eagle – for rabbit hunting. When Barnstaple’s sharp-eyed collaborator goes AWOL on wing the locals believe that it is responsible for losses among their sheep. Barnstaple must fend off the vigilance committee while he coaxes home his prize bird. (Torquil and Joan meet the committee during their bus-ride.) Powell had a knack for inventing implausible gimmicks of this sort (for example, the “Glue Man” plot in A Canterbury Tale [1944]) and then drawing from them little comedic vignettes to put in counterpoint with the main narrative. So plausible does the implausible become, however, that the comedic diversion generates noticeable viewer-tension about the absconded raptor’s fate – the more so because Barnstaple has named the creature “Torquil,” after his old friend, the Laird. Livesey’s expression when Barnstaple divulges this gesture of amity is almost worth the price of admission.

A production fact of the film is that a London stage-obligation prevented Livesey from being present during location shooting. Livesey himself trained a stand-in to double for him on location for exterior shots at a distance, with results so perfect that without the knowledge no viewer would guess it. Livesey would work with Powell again in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and A Matter of Life and Death (1946).

The relentless squalls indefinitely postponing Joan’s departure, and she warming to Torquil, she accepts the officer’s invitation to proctor her at the ceilidh, the traditional festival, with pipes and dancing, held in honor of a local couple’s sixtieth wedding anniversary. Powell makes the ceilidh the centerpiece of the story and the occasion of Joan’s change of heart. In filming the sequence, Powell had on set three pipers, members of the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, and dancers who knew how to foot the Schottische, all dressed as locals and all packed into a close room to suggest their familiarity in an intact community. The guests give quick voice to three Scots folksongs, the separate parts of which the men and women know by heart. One song is a heart-breaking lament in the minor mode. The old man, a Campbell, heartily welcomes MacNeil, and pleads with Joan to join the celebration. [View clip here]

The hot full-bloodedness of the occasion cracks the ice of Joan’s vanity. She speaks few lines, but Powell directs his cameraman, Erwin Hillier, to shoot her in medium body close-up, so that viewers see immediately, in the emerging rapt expression on her face, that the glacial heart has indeed melted. If there were a secular version of grace, this scene would body it forth. Joan must yet struggle with herself in a denouement of recrudescent petulance, putting herself and innocent others in real danger in sacrifice to selfishness. The abiding love and happiness that the ceilidh has revealed finally convince her, however, of what Torquil has earlier said concerning the islanders: “They’re not poor, they just don’t have any money.”

A few humble paragraphs can only scratch the surface of I Know Where I’m Going. The film commemorates the natural beauty of “the isles” in continuous ravishing black-and-white imagery; and supporting players such as the redoubtable Finlay Currie bring Gaelic authenticity to the scenes of pelagic life. Students groan out loud ritually at the beginning of black-and-white films, but my students soon fell quiet in a kind of enthrallment to the story. The coeds in particular warmed to it. As in The Edge of the World, Powell convinces viewers of the historical depth of the local culture, which they can see has been in place, steadily, for a long time, melding with the landscape and nourishing itself on the windblown beauty of fell and wave. MacNeil’s lairdship is a medieval survival, but a lively one, and nothing like an anachronism. The name Torquil (Thor is its root) reflects Mull’s Viking history, as does the local legend concerning “Brecca,” a Norwegian prince, whose plight becomes relevant to the Livesey and Hiller characters, in the whirlpool of their emotions.

Recently my wife and I watched a much commented on and fulsomely praised Québecquois film, La grande séduction (Seducing Doctor Lewis [2003]), directed by Jean-François Pouliot. A remote island-town, the fictitious Sainte-Marie de la Mauderne, has suffered the collapse of its fishing economy and desperately needs new enterprise. A plastics manufacturer agrees to build a factory, provided only that the town employ a fulltime medical doctor, of which amenity it is currently in default. Recruitment poses a difficulty. By luck, fraud, and one fortuitous opportunity for blackmail, the mayor and his cohorts at last bring a playboy-type, thirty-something physician – Doctor Christopher Lewis, played by David Boutin – from Montreal to Sainte-Marie de la Mauderne. La grand séduction is a dialect-movie, with the characters speaking the unmistakable patois of the true Canadians. In Pouliot’s setting, as must Powell’s Joan in Tobermorey, the vapid sophisticate Lewis must shed his pretensions in order both that he might discover himself and find a new vital context for a hitherto jejune existence. It is a conversion story, after all. [View trailer here]

La grande séduction exerts considerable charm. The film indeed tells its comic tale with some appreciable subtlety. But in watching it one constantly thinks that Pouliot must know his Powell filmography well and that anyone who knows I Know Where I’m Going must prefer Powell’s Mull to Pouliot’s Sainte-Marie de la Mauderne.

I send my fondest Christmas

Submitted by Thomas F. Bertonneau on Thu, 2009-12-24 15:08.

I send my fondest Christmas greetings to “KO,” “Kapitein Andre,” “Traveller,” “Steve,” and “David Smith.” “Kapitein Andre” quotes my favorite line from The Guns of Navarone. Sincerely, Tom Bertonneau

Another Conservative Obligation: "The Guns of Navarone" (1961)

Submitted by Kapitein Andre on Wed, 2009-12-23 21:45.

I tend to ignore the clumsy special effects and the preposterously high attrition rate of the Wehrmact at the hands of the British commandos and Greek resistance fighters, and concentrate on the dialogue, in particular that between Captain Mallory (Gregory Peck) and Corporal Miller (David Niven).

Perhaps this ultimatum by Peck’s Mallory to Niven’s Miller might refresh readers’ memories: “You think you’ve been getting away with it all this time, standing by. Well, son, your by-standing days are over! You’re in it now, up to your neck! They told me you’re a genius with explosives. Start proving it! You got me in the mood to use this thing [pistol], and by God, if you don’t think of something, I’ll use it on you!”

David Niven

Submitted by SteveP55419 on Thu, 2009-12-24 01:58.

There is an irony in that exchange of dialog in that Niven (who played the shirker in the movie) was a genuine war hero in real life. I don't know what Peck did in WWII, but the scene must have been awkward for him knowing Niven's background.

Dr Bertonneau

Submitted by david smith on Wed, 2009-12-23 17:54.

On a bleak day your essay was truly a pleasure. Thank you for it and your writings over the time I have been following the Journal.

Eric Voegelin

Submitted by SteveP55419 on Wed, 2009-12-23 17:29.

I put this movie in my Netflix cue. This recommendation is not necessarily tied to civilizational values (although it is in a way) but if you want to return to the Scottish Isles of the late 1940s and appreciate droll humor, see the British (Ealing Studios) comedy: 'Tight Little Island', aka: 'Wiskey Galore'.

You put me on to Eric Voegelin a couple of months ago, for which I thank you, and I devoured him. Quite a bit of it was way over my head but I got the message. Here is an issue: I emailed three quite well-regarded conservative pundits (one is well-known locally here in Minnesota but the other two are in the very top eschelon nationally and you would recognize their names right away) and all three gave very nice replies stating, in so many words, that they have not read him but always intended to and now they will. I was shocked.

If these good people have not read him, who has?

Is there anyone out there working to get him mainstreamed? Someone should write 'Voegelin For Dummies'.

Thanks again for all that you do.

PS: Not implying that only dummies need help understanding him. No offense intended to anyone.

Voegelin on VFR

Submitted by KO on Thu, 2009-12-24 12:29.

@ SteveP: For a discussion of contemporary liberalism as a form of Voegelinian Gnosticism, go to View from the Right at www.amnation.com/vfr. The thread is titled, "We are seeing liberalism morph into totalitarianism."

In answer to your question: in addition to Dr. Bertonneau, Lawrence Auster at VFR and Jim Kalb at Turnabout have read Voegelin, and yours truly can make some recommendations, too: (1) The New Science of Politics; (2) Order and History v. 1, Israel and Revelation; (3) v. 3, Plato and Aristotle; and (4) Anamnesis, which I have not read but which Dr. Bertonneau might place in the no. 1 spot.

Merry Christmas to all!

@ Dr. Bertonneau

Submitted by traveller on Tue, 2009-12-22 15:32.

I have never enjoyed such a diverse vision on art, life and philosophy as what you regularly produce.

To top it you are writing the smoothest and most elegant English I had the pleasure to read since a very long time.

Congratulations and thank you very much for sharing it with us.

Re Dr. Bertonneau

Submitted by KO on Wed, 2009-12-23 12:05.

Traveller, you are a man of taste. It is indeed a treat to have Dr. Bertonneau for our teacher.