Poe And His Frenchman, Baudelaire And His Americans: La Théorie De La Décadence Bohème

From the desk of Thomas F. Bertonneau on Sun, 2013-12-22 03:19

Remember: I think these thoughts so that you don’t have to…

The spectacle of decadence has appealed to poets since the time of Juvenal, the heyday of whose authorship came early in the Second Century AD. The hypertrophy and grotesquery of the Imperial City thus provide the background for Juvenal’s remarkable Satires, which presciently mirror the cultural degeneracy of the early Twenty-First Century’s civic scene, quite as well as they do for that of their own Latinate-Imperial milieu. Did Juvenal’s eyes witness him the Urbs on the Tiber or the City by the Bay? Is he writing about Rome’s Stoic salons or UC Berkeley’s Philosophy Department during the visiting professorship of Michel Foucault or again about the disintegration of the humanities departments generally under Deconstruction? “Infection spread this plague, / and will spread it further still… You will be taken up, over time / by a very queer brotherhood,” as Juvenal writes. Rome had its mysteries two thousand years ago, but then so does West Hollywood today: “You’ll see one initiate busy with an eyebrow pencil [while] a second sips his wine / from a big glass phallus, his long luxuriant curls / caught up in a golden hairnet.” Nor is the modern milieu less free than Rome was under Domitian, say, or Hadrian, of secret police, informers, and goon-squads. A ready inclination to cry lèse majesté belongs to the ripeness of a politically and culturally corrupt scene. So too do the insipidity of literature and the jejuneness of art.

Juvenal’s scathing wit, which approximates the metaphysical, has exercised its influence down through the centuries, the satirist’s spirit being noticeable, for example, in Samuel Johnson’s “London” (1738), which the learned doctor patterns after Satire III, and in contemporaneous prose passages from Jonathan Swift. The “City” passages of T. S. Eliot’s Waste Land owe a debt to Juvenal, including the allusions to gross homosexual solicitation. To invoke Eliot, however, is to invoke Eliot’s models, the French Symbolist poets, who took their vision from the eldest of them, their spiritual father as it were, Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867). That keen-eyed king of flâneurs knew his Juvenal well, as he knew literature well, all of it. Concerning Baudelaire’s prose poem “Portrait of a Mistress,” for example, Rosemary Boyd in her study of the poet (2008) remarks that the “Portrait” reads like an “urbane version of Juvenal’s sixth satire, with its attacks on women and its suggestion that a perfect wife, that rara avis, would prove not just tedious but infuriating in her ability to show up the faults of her husband.”

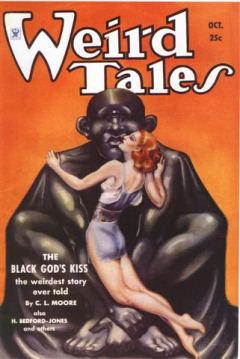

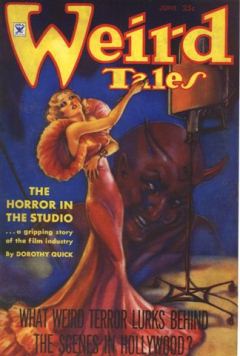

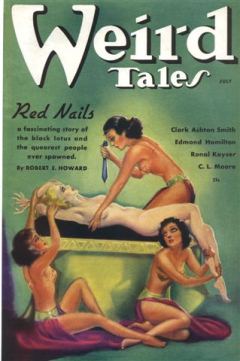

Whereas Baudelaire furnishes the solar primary of the group of writers to whom these words devote themselves, the brief history of decadence, as diagnosed by literary Bohemia, that they trace begins with that other great pillar of the Baudelairean edifice – the first being Joseph de Maistre – the American writer, or prodigy, or drunken bard and opiate seer Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849). The same brief history will extend beyond Baudelaire to two additional American writers of the Twentieth Century, who nourish themselves on the Symbolist critique of culture, whom criticism itself, however, has superciliously refused to admit to what goes by the name of the canon. It is a pity, because Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961) and Catherine Louise Moore (1911 – 1987), despite having published most of their work in the lurid pulp monthly Weird Tales, were incisive observers of social conditions and civilizational trends; they were also accomplished stylists, worthy of their precursor-models, Poe and Baudelaire. By including them under the rubric of “the bohemian theory of decadence,” the discussion honors the Baudelairean spirit, which disdains to confine itself in vetted precincts, or to despise what correctness disdains, preferring rather to find truth where it is.

Baudelaire’s translation of Poe’s pseudo-Platonic dialogue ”The Colloquy of Monos and Una,” which appeared originally in Graham’s Magazine in 1841, saw print in the devotee’s French in 1857, the same year as Les fleurs du mal; the “Colloquy” belongs in tandem with another dialogue-story, “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion” (1839), in respect of which it functions as a sequel. Both tales take as their premise the destruction of humanity by universal conflagration when the earth passes through the tail of a comet and a chemical reaction withdraws nitrogen from the atmosphere. In Poe’s conception, rooted in his bold synthesis of Epicurus’ atomistic cosmology and Swedenborg’s theory of astral planes, the personality survives the body after death to rise to a new, higher level of existence. In “The Colloquy,” Monos appears to have died and resurrected before Una, whose rebirth in elevated consciousness he supervises. Orienting the reborn requires a careful review of the former environment in time and space. It is in helping Una to recover her sense of personal specificity that Monos affirms how, despite having predeceased her by a few years, “Unquestionably, it was in the Earth’s dotage” that both of them died; and how the “anxieties,” as he says, which hastened his own demise, “had their origin in the general turmoil and decay” then afflicting the world. The “turmoil and decay” took their genesis in turn, as Poe has Monos put it, in ubiquitous “misrule” under a program of “improvement,” which claimed for itself to be “the progress of our civilization.”

Now and then, as Monos says, some “vigorous intellect” would protest against this “progress” on behalf of the sane precept “which should have taught our race to submit to the guidance of natural laws, rather than attempt their control.” These admirable “master-minds,” articulating, in the story’s diction, “the poetic intellect,” saw in the reign of “practical science,” not a utopia of human fulfillment but rather a “retro-gradation of true utility.” Poe’s future dissidents, like Socrates in Athens in the dénouement of the Peloponnesian War or Juvenal under Domitian, will have found themselves “living and perishing amid the scorn of the ‘utilitarians’” – that is, “of rough pedants who arrogated to themselves the title which could have been properly applied only to the scorned.” Like the Juggernaut, however, “progress,” heralding itself as an exalted “movement,” will have galloped petulantly down its improvised path, “a diseased commotion, moral and physical,” trampling everything in its career. While a new global industrialism of “huge smoking cities… innumerable” enfolds the earth, humanity lapses into “infantine imbecility,” in the calamity of which any vestige of wisdom succumbs to the triple thoughtlessness of “system,” “abstraction,” and defective “generalities.” Having spurned the rule of hierarchy or, as Poe calls it, “gradation,” implicit in the cosmic order; having done so the “movement” not only desecrates “the fair face of Nature,” but it also discharges its ugliness in “wild attempts at an omni-prevalent Democracy.”

Did the opportunity never occur when the “poetic intellect” might have stemmed this all-pernicious “Democracy”? When Monos speculates, it becomes clear why Poe appealed so powerfully to Baudelaire. Poe has Monos tell Una that the dissenters failed in their rigor and gave up their ground. They relinquished control of “the schools,” where formerly “taste” (Poe italicizes the term) had been inculcated through the curriculum. “For in truth,” the speaker continues, “it was at this crisis that taste alone – that faculty which, holding a middle position between the pure intellect and the moral sense, could never safely have been disregarded – it was now that taste alone could have led us back to Beauty, to Nature, and to Life.”

One of Baudelaire’s aphorisms, hinting at the problem of ressentiment released from all its checks, seems to respond to Poe’s description of civilization in bloated, egalitarian decay. “What can be more absurd than Progress,” Baudelaire writes, “since man, as the event of each day proves, is forever the double and equal of man – is forever, that is to say, in the state of primitive nature.” In another aphorism Baudelaire foresees the day, in near prospect, when “machinery will have Americanized us”; whereupon, “so far will Progress have atrophied in us all that is spiritual, that no dream of the Utopians, however bloody, sacrificial, sacrilegious, or unnatural, will be comparable to the result.”

It was Baudelaire’s immediate heir, Stéphane Mallarmé (1842 – 1898), who in a sonnet depicted the Parisian translator of Poe and the author of Les fleurs du mal as the martyr of Second-Empire vulgarity. In the “Tombeau de Baudelaire,” the grave marker rises out of “the sewer’s dark sepulchral mouth,” with Baudelaire’s ineradicable shade hovering over it, as Mallarmé writes, “a poison tutelary”; that is, the anti-toxin to toxic culture, to gutter-culture. Mallarmé also dedicated a sonnet to Poe, who, from the point of view of the reigning corruption, stood out as a great perpetrator of “Blasphemy.” Now Baudelaire, like Mallarmé, nursed a traditionalist’s fondness for the sonnet and wrote them numerously throughout his authorship.

Baudelaire composed one of his best-known sonnets, the gnomic “Correspondences,” as early as 1842 but only saw it in publication in the first edition of Les fleurs, in 1857. Critics interpret “Correspondences” almost invariably as a Swedenborgian allegory, which at one rather insipid level perhaps it is. The notion of a Swedenborgian poème-à-clé nevertheless fails to exhaust the text. A darker, more provocative interpretation, drawing on Baudelaire’s admiration of Poe’s cultural critique, and indeed on Baudelaire’s affiliation with de Maistre, sees in “Correspondences” a characterization of modernity as a regression into archaic forms, most particularly into the paroxysm of an orgiastic recrudescence.

La Nature est un temple où de vivants piliers

Laissent parfois sortir de confuses paroles;

L'homme y passe à travers des forêts de symboles

Qui l'observent avec des regards familiers.

Comme de longs échos qui de loin se confondent

Dans une ténébreuse et profonde unité,

Vaste comme la nuit et comme la clarté,

Les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent.

Il est des parfums frais comme des chairs d'enfants,

Doux comme les hautbois, verts comme les prairies,

— Et d'autres, corrompus, riches et triomphants,

Ayant l'expansion des choses infinies,

Comme l'ambre, le musc, le benjoin et l'encens,

Qui chantent les transports de l'esprit et des sens.

Baudelaire’s sonnet, although belonging to the genre of lyric, exhibits a type of minimal story-telling. Where the standard interpretation errs, in fact, is in not taking sufficient heed of the poem’s action. The opening lines of “Correspondences” invoke a scene, what Baudelaire names “La nature,” or in the English translation “nature,” through which wanders the figure that qualifies as the protagonist of the action whom Baudelaire dubs “l’homme.” That would be “the man,” not “man,” generically or in some abstract singular, as every English translator since Lewis P. Shanks has rendered it. This man – “the man” – finds himself in the midst of “nature” as though traversing the precincts of “a temple [of] living pillars” (“vivants piliers”) that, in the poem’s language, “regard him with familiar glances” (“regards familiers”) and from whom he hears emitted as he passes “confused words” (“paroles confuses”). Baudelaire has conjured an extraordinarily sinister atmosphere, worthy of Poe at his creepiest. But what is the poem’s “nature” and whose confusion do the “confused words” signify?

Baudelaire, in taking up the position of de Maistre, and again of Poe, that Christendom trumps troglodyte-ism, and likewise hierarchy democracy, necessarily repudiated the position, on everything, of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. When “Correspondences” refers to “nature,” borrowing and turning the Rousseauvian usage, it refers to the lapse from culture backwards into a previous, less developed state. The shift would be defective, not redemptive. By equating “nature” with a “temple,” moreover, Baudelaire hints at retrogression into antique religiosity, which, not incidentally, is precisely how de Maistre saw revolutionary politics. Let it be recalled also that the theme of persecution appears in Poe’s egalitarian dystopia, as an appurtenance of the falsely self-denominating “Progress.” As for who is confused, that they are those who utter the “confused words,” not the one who hears them, best fits plausibility. Taking these observations in their ensemble, the reader puts himself in a good way to answer an important question about the poem: What happens to “the man” when he loses himself in what Baudelaire calls the “unity tenebrous and profound” (“ténébreuse et profonde unité”), into which the “confused words” have suddenly resolved themselves, only to disappear from the poem?

In the language of rhetorical analysis, “the man” suffers disintegration into a network of metonymies: “Perfumes, sounds, and colors,” which “correspond” to one another. Whereupon, as Baudelaire makes his tercets say, the effects of “the man’s” disappearance generate – for someone – a “transport of the soul and senses” whose provocations take justly to themselves the trio of adjectives “corrupt, rich and triumphant” (“corrompus, riches, et triomphants”). In non-technical language, “the man” is the victim – the fall-guy of a lynching – of the babbling multitude who, in the befuddled undifferentiation of its self-induced egalitarian crisis, its spiritual jejuneness, its frothing ressentiment, sets upon the actual individuated person in hopes of acquiring from him the sense of being that it feels itself intolerably to lack. The mob, like the second-person “hypocrite” of that introductory poem to Les fleurs, “To the Reader,” is utterly two-faced, publicly despising individuality while privately craving its valor, or its flavor, but this hypocrisy too is a symptom of decadence. It signifies, for Baudelaire, the degraded present.

According to Roberto Calasso in La folie Baudelaire (English, 2012), Baudelaire’s literary nemesis Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804 – 1869), the high guardian of la littérature française, wanted Louis-Napoleon to license writers and enlist them under penalty of law in the service of the state. Dissent would have been punishable as a type of lèse-majesté. Or maybe the phrase would be lèse-laïcité. Or infraction contre la foule, defining la foule as whatever gang currently holds power and abuses it to manipulate the people. The literary precinct where the discussion now goes – past the near-pornographic covers of Weird Tales, a 1930s “pulp” monthly, and into its double columns of penny-a-word print – had warning signs posted around it by the monitors of decency in its own time and would undoubtedly be condemned today by, say, feminists, supposing they knew of its existence. But then the French state also prosecuted Les fleurs du mal. Nevertheless, when the spirit of Poe, having migrated astrally through its French incarnation, returned belatedly to its native shores, it did so in the activity of the best Weird Tales contributors. Of the two who are most relevant in the present context, Clark Ashton Smith comes first chronologically and C. L. Moore second, but as Smith, a gentleman, would have said: Ladies first.

The Great Depression ended Moore’s plans for a baccalaureate and she went to work in a savings and loan bank as a secretary typist. She wrote poetry and stories in her spare hours. She corresponded with H. P. Lovecraft in the last three years before his death and argued with him about the New Deal. An avid Roosevelt supporter, HPL was for it; Moore, defending the market, was against it. A recent scholarly article has shown a consistent pattern of Baudelairean allusions, in diction and phraseology, pervading Moore’s work of the 1930s. Indeed, the whole pattern of the story-cycle that made her as famous as Lovecraft among Weird Tales readers derives itself plausibly from the scenario of “Correspondences.” How to describe Moore’s protagonist Northwest Smith? He is partly a flâneur (he likes to sit in dive-bars drinking segir, Venusian whiskey), partly an anticipation of Indiana Jones (insofar as he has a profession, it seems to entail dealing in contraband archeology); he is thoroughly masculine, and, as the aforementioned scholarly article would have it, a “Paracletic hero.” That means that Smith has the knack of running falling afoul of and robustly disestablishing sacrificial polities and cults. Moore’s future has at once a politically chaotic and a resurgently cultic character; its principalities, often effeminate or matriarchal, have an appetite for victims.

The fifth story of the Smith cycle, Jhuli, which appeared in Weird Tales for March 1935, is exemplary. When Smith awakes, his head throbbing from having been slipped the proverbial Mickey, he finds himself like “the man” in Baudelaire’s “Correspondences” sensing “eyes upon him” in the gloom, “not physical eyes, but a more all-pervading inspection.” When preternatural light dissipates the murk, Smith sees “columned vistas stretching away all around,” as if the place were “a wilderness of pillars.” The titular Jhuli, rules here. Hers is a usurping privilegentsia that, having hijacked its society, exploits everyone external to the despotic inner-circle. These hieratic elites both need and despise those whom they have subjugated; incapable of original affect, they spend their lives “wholly,” as Jhuli tells Smith, “in the experiencing and enjoyment of sensation,” which they draw vampire-style from their victims in rites of humiliation and torture. When Smith glimpses the captive masses they strike him as “fitted for some lofty purpose” so that, by contrast with them, the cultists appear “degenerate,” “obscene,” and “bestialized.” The cultists see themselves, via a justifying superman-theory, as the exalted perfection of rationality whose status entitles them to the living substance of their inferiors.

Moore’s dystopia conforms to what Baudelaire would have recognized as a satanic inversion; it seconds the Baudelairean insight that “the Revolution and the Cult of Reason confirm the doctrine of sacrifice.” In their bestiality, the cultists embody yet another Baudelairean aperçu, namely that whereas “the invocation of God, or spirituality, is a desire to climb higher; that of Satan, or animality, is delight in descent.”

Of Clark Ashton Smith, whose capacity for baroque fabulation anticipates Moore’s, which in turn likely owes a debt to it, Brian Stableford has written: “He seems to have discovered a strong affinity with the particular current in nineteenth century French poetry which extended from the lusher products of Romanticism to the morbid extravagances of the Decadent Movement.” Indeed, Smith’s earliest work was poetry, often according to the sonnet convention, in a Baudelairean style. As in the case of Moore, Smith’s commentators little suspect a perceptive social critique in his oeuvre yet such a critique is present. Rather than suggesting that critique by way of one of Smith’s characteristic Weird Tale narratives – decked out as they are in his usual trappings of cosmic fantasy – it will requite these present musings with an apt dénouement to cite a minor although by no means insignificant item of his oeuvre, what a failure of perception might deem an entirely drab or naughty little story under the unassuming title of “Something New.” As incidental as it is, Smith’s “Something New” nevertheless communicates with the Baudelairean ethos. It communicates in an especially felicitous way with Baudelaire’s Juvenalesque etiology of decadence, in which the feminization of culture poisons institutions at the root. To recall Baudelaire, “Woman is the opposite of the Dandy,” that is, of the flâneur; she personifies “childishness, nonchalance, and malice.”

“Something New” (Story Book, October 1924) presents the poet en chambre with his mistress of the last four months. She reclines in the pose of an odalisque on the sofa, “looking” – as Smith gives it to his proxy to think – “like a poem to Ennui by Baudelaire”; he reclines with her, compromising his masculinity. In the tale’s opening line, the mistress had “moaned” to the poet, “Tell me something new.” Like the lamia in Moore’s Jhuli, if in a slightly more ordinary but no less petulant way, the mistress is très ennuyée, and in her deficit of external stimuli she demands a performance from the lover. He essays a few appropriate but rather hackneyed tropes. She dismisses “old stuff.” This one is not the first poet among her devotees, after all. Ignoring the comparison, the poet suggests that in the default of dainty conceits the plaintive paramour might want “some caveman stuff,” but even while suggesting it, he rebels at the call slavishly to serve. In a perfect complement to the evocation of Baudelaire, a Nietzschean aphorism flashes from his memory: “When thou goest to woman, take thy whip.” Muses the poet to himself by way of like-mindedness: “By Jove, the old boy had the right dope.” Incidentally, in placing the allusion to Saint Charles before the quotation from Saint Friedrich, Smith has correctly prioritized the relation.

Baudelaire, following de Maistre, regarded modernity as a recursion to sacrifice; and quite on his own, Baudelaire also regarded modernity as effeminate, as an abdication of manhood hence also of procedure, discrimination, and moral rigor. For Juvenal, too, with an invocation of whom the present discourse began, the decadence of society appeared, if not exclusively, yet signally, in effeminacy and the abdication of manhood, noticeably in the prevalence of eunuchs and homosexuals among the trend-setting, taste-making elites of the Imperial City, but also in the appropriation of religion by women. (The scholarly consensus, by the way, is that Juvenal was himself homosexual.) In Juvenal again, the reader discovers an anticipation of Baudelaire. What is the satirist’s image of the descent of the social order into formlessness and grossness? In Satire VI, Juvenal records a symptomatic ruckus in the forum: “Now here come the devotees / of frenzied Bellona, and Cybele, Mother of Gods, with a huge eunuch, a face for lesser obscenities to revere.” Rome has indeed, in Juvenal’s day and as he sees it, become one great continuous multicultural and feminist celebration, marked by the “solemn rant,” “Horoscopy,” and ready access to “the abortionist’s arts.”

To return to the topic of the Californian: In a Letter to Samuel J. Sackett, Smith once listed his “formative influences”: “I think Poe should head the list. Baudelaire and George Sterling, in regard to poetry, and Lovecraft and Dunsany in regard to prose, should be added… Lafcadio Hearn, [Théophile] Gautier, and [Gustave] Flaubert (the latter at least in The Temptation of St. Anthony) have all helped to shape my prose style.” The side-reference to Flaubert acquires particular relevance in the present context because, in elaborating the Saint’s vision, it entails a panoply of Late-Antique heresies and perversions, including a major episode in which the devil in the guise of the Queen of Sheba tries to subvert the holy man’s attempt to think his way past the toxic deliquescence of his milieu. Smith lived his entire life rather like a hermit in the small town of Auburn in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in Northern California, making occasional trips to San Francisco or Los Angeles. What he saw of cities little impressed him. “I, for one,” he wrote to his mentor George Sterling in December 1925, “refuse to submit to the arid, earth-bound spirit of the time.”

In May 1926 in another letter to Sterling, Smith discusses whether in an anthology he should be described as a Californian: “But I suppose one might as well be that as anything… Moronism, unhappily, is not confined to California.”

But what comes next in “Something New”? We recall that in Poe’s “Colloquy,” the text implies the question whether the moral decay that overtook the world might at some point have been stemmed. It might have, Poe further implies, but in the moment the right-thinking failed in action. Not so Smith’s poet. Abruptly, “he drew her across his knees like a naughty child.” So “muscular” was the gesture that the mistress “had neither the time nor the impulse to resist or cry out.” Pronouncing sentence – “I’m going to give you the spanking of your life” – the poet executes the same. “A dozen smart blows, with a sound like the clapping of shingles, and then he released her and rose to his feet.” The chastised beneficiary of the tonic immediately repents her petulance. “I didn’t think you had it in you,” she confesses. As for the poet, “he had the presence of mind to adjust to the situation.”

Now Smith himself deferred often to Baudelaire, and so shall I, giving the final words to the Exalted Master. There is a true progress, Baudelaire argues, and a false progress: “In order that the law of Progress could exist each man would have to be willing to enforce it; for it is only when every individual has made up his mind to move forward that humanity will be in a state of progress.”

An American genius? pas possible!

Submitted by Steve Kogan on Sat, 2013-12-28 22:55.

Baudelaire writes that he discovered Poe in 1846 or '47, when most of the first French translations appeared, and he was apparently stunned to discover that the author was an American. "Ce n'est qu'un yankee!" he exclaimed to fellow writer Charles Asselineau after a gathering in which Poe's "The Black Cat" had been a subject of conversation. Asselineau writes that Baudelaire made the remark on the staircase while pushing his hat onto his head "avec violence." That the home country of a soulless "Americanization" could also have produced an Edgar Allan Poe must have confounded him, for he made the rounds among foreign booksellers and others to verify the fact for himself and finally tracked down an American who said that he had known him in the States.

My information comes from Margaret Gilman's Baudelaire the Critic (Columbia U.P, 1943), which I ferreted out from an overflowing library of a friend in northern California. I continue to be awed and delighted, however, by the far greater riches that pour forth from the music and literature collections of Tom Bertonneau, who can find the voices of Poe and Baudelaire reborn under the deliciously lurid covers of Weird Tales and, like "the Baudelairean spirit" that he honors, himself "disdains . . . to despise what correctness distains, preferring rather to find truth where it is."

Juvenal et al.

Submitted by KO on Sun, 2013-12-29 17:44.

Wonderful essay, Prof. Bertonneau. It is sad that Juvenal and Baudelaire illumine modern America and Europe so aptly, but better that than groping in the dark.

For Baudelaire reborn, see the recent terza rima narrative, The Lalaurie Horror, by Louisiana poet, Jennifer Reeser.