How Flanders Helped Shape Freedom in America

From the desk of Paul Belien on Sun, 2005-07-10 23:01

July 11 is Flanders Day. The date refers to the day in 1302 when an army of Flemish burghers defeated a superior army of French knights by driving them into a swamp. Historically the term Flanders refers to the mediaeval county of Flanders centered around the town of Brugge (Bruges in French). Today, the term Flanders is used in a broader sense, referring to the Dutch-speaking part of contemporary Belgium i.e. the historical counties of Flanders, Brabant and Loon. Brussels, the historical capital of Brabant, is currently the capital of Europe, Belgium and Flanders (in its contemporary, broad sense).

Most Americans do not know that they owe a lot to the freedom-loving Flemings. A significant portion of the roots of American democracy can be found in the mediaeval Flemish towns of Brugge and Ghent and in the Brabant towns of Brussels and Antwerp. To find these roots we must return to the early Middle Ages, the period following the disintegration of Charlemagne’s empire. Ironically, the European Union claims to go back to the same roots.

Indeed, part of the original mystique of the movement for European unification can be found in the name that was given to the Brussels building which for almost 50 years has housed the European Council of Ministers. The building is called the

Charlemagne is considered the father of the political unification of Europe just as he is considered the father of both France and Germany, the two nations whose alliance constitutes the political backbone of the process for European unification after the Second World War. The territory of the original six member-states of the European Economic Community (France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg) was an almost exact copy of this Carolingian Empire. Only Switzerland was missing.

But Charles the Bald and Louis the German were not the only grandsons of Charlemagne. They had a brother, Lothar, who inherited the imperial crown and the lands lying between France and Germany – the Middle-Frankish kingdom. This Kingdom of the Middle was named after him: Lotharii Regnum or Lorraine. Lothar’s realm comprised all the countries lying between France and Germany today (the three Benelux-nations plus Switzerland) as well as the Eastern part of present-day France and the Western part of contemporary Germany plus the northern half of Italy.

When Lothar’s son died without offspring in 875 the middle territories were divided between Charles the Bald and Louis the German. However, as these regions lay on the periphery of their heartlands generations of kings of France and emperors of the so-called “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation” trying to consolidate their powers were never able to establish a firm rule over them. The result was that throughout the Middle Ages, and for some of them up to the 18th century and even today, the lands of the ancient middle part of Charlemagne’s empire were made up of virtually self-governing republics of farmers (as in Switzerland), independent countries controlled by burghers (as in the Netherlands and along the Rhine) or city republics (as in the North of Italy).

Virtually self-governing, with little interference from greedy princes, their tax collectors and meddling civil servants, these lands became very prosperous. Capitalism originated here. This whole axis from Amsterdam in the north to Siena in the south evolved into the economic spine of continental Europe. During the course of history in some of these middle regions (notably in the Netherlands in the Burgundian era and at the time of the United Dutch Republic, and in Switzerland) these small, independent states merged gradually into federations where the constituting parts and the individual citizens retained a large degree of autonomy. In these regions sophisticated political theories were devised which ensured that the Prince or the government did not embody the highest authority and were accountable to the Law. Switzerland has been a republic since the 13th century and the Netherlands was a republic from the 16th to the 18th century. The Burgundian Netherlands had a Prince, but whenever he wanted to raise taxes this prince, the Duke of Burgundy, had to ask the 17 counties of the Federation (and in the most prosperous of these counties, like Flanders and Brabant, even the different cities) for permission. The former Carolingian Middle Lands saw not only the birth of capitalism but also of limited government.

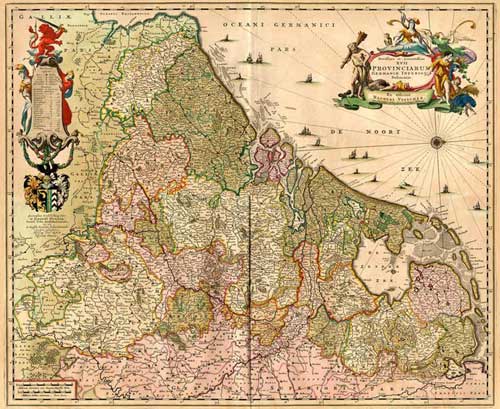

Historically, the formation of the Dutch nation started at the end of the 14th century when the Dukes of Burgundy through a series of marriages united 17 hitherto independent territories in the delta of the Rhine, Maas (Meuse) and Scheldt rivers, that were commonly referred to as the Nederlanden in Dutch (literally: the Low Countries) or the Provinciae Belgicae in Latin. This area comprised contemporary Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg as well as a part of northern France.

Because these 17 provinces were situated on the periphery of the two kingdoms that they nominally belonged to (i.e. the Kingdom of France for Flanders and Artois, and the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation for the other 15 counties and duchies) they became a cluster of very prosperous and virtually independent city states where neither the overlord (the King of France or the Emperor) nor the feudal lord of the various counties and duchies had much to say. The burghers of towns like Brugge, Ghent, Antwerp, Brussels, Leuven, Mechelen, Breda, Middelburg, Rotterdam and Amsterdam ruled themselves. Very soon a republican tradition developed, where the nominal lord was tolerated only so long as he did not harm the interests of the cities, allowed them to rule themselves, and respected the charters and liberties which his predecessors had granted.

The Privilege of the Burghers

As early as the beginning of the 12th century, the citizens of Flanders had already formulated the principle that they were entitled to depose their Prince if the latter did not fulfil his duties towards the people. When in February 1128 Count William Clito of Flanders, son of Duke Robert Curthose of Normandy and grandson of William the Conqueror of England, introduced a new tax, despite an earlier promise not to, the Flemish cities rebelled. The burghers demanded that the Count be brought before an independent court, consisting of “barons from both parties and responsible men from the clergy and the people,” to decide whether or not the Count had broken his promise and, if so, to depose him. Instead of recognizing that the Prince had been appointed by God the Flemings insisted that he, too, was subject to the law and, if he did not accept this, he would be removed by an impartial court.

The Count objected and raised an army to teach his subjects a lesson, but he was defeated and killed in a battle with the Ghent militia in July 1128 whereupon the nobles and cities of Flanders convened to choose themselves another count from a different family. When the King of France, the overlord of the County of Flanders, tried to interfere the city of Brugge issued a proclamation, stating quite bluntly: “Let it be known to everyone […] that the King of France has nothing to do with the appointment or election of a Count of Flanders. […] This is the privilege of the nobles and burghers of this land.” During the following three centuries various Kings of France tried to meddle with Flemish affairs but never succeeded in establishing a permanent hold on the richest county of their kingdom.

From Brugge and Ghent the new principle of “government by consent” and under the Rule of Law spread into neighbouring Antwerp, Brussels and other Brabant cities and towns. From 1356 onwards every new Duke of Brabant, upon his accession, had to take a solemn vow, the so-called Joyful Entry. In this vow the prince promised to respect the liberties of the citizens and formally acknowledged that they had a right to rebel and “separate” from him if he did not do so. By the time the Dukes of Burgundy became lords of the various Low Countries it was an accepted principle in all the 17 provinces that the prince succeeded as Lord of the Netherlands only at the moment that he took this vow.

When in the middle of the 16th century the direct descendant of the Burgundians, the Habsburg King Philip II of Spain, tried to introduce Spanish absolutism in the Netherlands, the Dutch states rebelled. Their States-General convened in The Hague on 26 July 1581 where they issued the Plakkaat van Verlatinge (Statement of Separation) to justify their secession from Spain. “It is common knowledge that […] the sovereign is there to serve his subjects, without whom he would not be sovereign,” the document stated. When the sovereign violates the rights of the people “he must be regarded not as a sovereign but as a tyrant. Then his subjects may freely choose no longer to acknowledge him as their sovereign – especially after the States of the land have taken counsel together – but to separate from him and in place of him to choose another to be their sovereign and to protect their safety.” The Dutch provinces decided to establish a confederation of sovereign republics. This new state, inhabited by Catholics as well as Calvinist Protestants, issued a proclamation of religious tolerance (the so-called Pacification of Ghent) and vested supreme authority in representatives whose mandate was provisional and temporary. The military leadership was assigned to a Stadholder (literally: a defender of the city), Prince William “the Taciturn” of Orange.

Eventually, however, Spanish troops succeeded in reconquering 10 of the 17 provinces. The fall of Antwerp in 1585 marked the end of independence in the southern provinces but the Spanish troops were unable to subdue the lands further to the North because the Dutch had flooded the estuary of the Maas and Rhine, thus creating a barrier of water against the Spanish. After the Spanish conquest of the South more than ten percent of the population of southern provinces such as Flanders and Brabant fled to the North and resettled in and around Amsterdam and other towns in Holland and Zeeland. The population of Antwerp fell from 84,000 in 1583 to 42,000 in 1589; Ghent from 45,000 to 22,000; Brugge from 35,000 to 17,000; Mechelen from 30,000 to 10,000. In the North, Amsterdam boomed from 30,000 to 60,000; Haarlem from 16,000 to 40,000; Middelburg from 10,000 to 30,000; Leiden from 13,000 to 26,000.

Crossing the Atlantic

While the southern (Spanish) Netherlands remained under foreign rule and became a colony first of the Spanish Habsburgs, later of their Austrian relatives, the confederation of the seven northern provinces – the Confoederatio Belgica or United Dutch Republic – became a global power. It established its own colonies all over the world, from America to South Africa, the Far East and Japan. The Dutch colonists took their political ideas along with them, also to Nova Belgica, New Netherland, with its capital Nieuw-Amsterdam, known today as New York.

It was a 30-year old adventurer from Amsterdam, Arnout Vogels, who in 1610 became the first fur trader along the Hudson river. Vogels was born in Antwerp and had fled Brabant with his parents after the Spanish conquest. In 1624 Nieuw-Amsterdam was founded by the West India Company, a Dutch trading company established by Willem Usselincx, an Antwerp businessman who had also fled to Amsterdam in 1585. According to Russell Shorto in his 2004 bestselling history of Manhattan, The Island at the Centre of the World, the Dutch gave America its cosmopolitan outlook and shaped it into the open and democratic society it is today. The democratic traditions of the Netherlands were brought to America by Adriaen van der Donck, a lawyer from Brabant.

There is a direct historical line linking Brugge to Antwerp, Antwerp to Amsterdam and Amsterdam to New York. The “centre of the world,” as a beacon of self-governing democracy and liberty where capitalism originated, evolved along this line. Brugge was the Manhattan of the 13th century, as Antwerp was the Manhattan of the 16th century and Amsterdam that of the 17th century. Likewise Antwerp was the Brugge of the 16th century, Amsterdam that of the 17th, and New York that of the 20th century.

A number of typically American things such as cookie (koekje), dollar (daalder) and Santa Claus (Sinterklaas) have a Dutch origin which dates back to mediaeval Flanders. The same is true for the concept that free trade liberates people and that political and economic freedom are indivisible. Professor Stephen E. Lucas of the University of Wisconsin at Madison writes in “The Plakkaat van Verlatinge: A Neglected Model for the American Declaration of Independence” (his contribution to Hofte, R., and H. Kardux, eds. The Netherlands in Five Centuries of Transatlantic Exchange. Amsterdam: VU Press, 1994) that the text of the Declaration of Independence issued by the American Continental Congress on 4 July 1776 was clearly modelled on the 1581 Dutch Plakkaat van Verlatinge. The American Declaration stated: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that […] whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends [i.e. to secure the liberties of the people] it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

This is exactly what the Flemings had said in 1128 when they deposed Count William Clito of Flanders and the burghers of Brugge declared that “the appointment or election of a Count of Flanders […] is the privilege of the nobles and burghers of this land.”

Religious freedom in The Netherlands

Submitted by Xavier Meulders on Mon, 2007-07-23 10:31.

It is indeed true that the Dutch republic was constituted in a spirit of religious freedom, but until now I'm still struck how this spirit was already subdued by the beginning of the 17th century, when the republic was only two decades young! Because how can we explain the persecutions of the so-called remonstrants (fellows of the doctrine of Jacob Arminius) after the Synod of Dordrecht (1619); the murder on Johan van Oldenbarnevelt by the disciples of prince Maurits and the restraint of intellectual leaders such as Hugo Grotius in the Loevestein castle? To my opinion, the spirit of genuine freedom in The Netherlands already turned into Leviathan after prince Maurits's coup d'état. In fact, it's no coincidence at all that the Mayflower (the ship) travelling from Plymouth (England) tot Plymouth (Massachussets) carried also a lot of Dutch passengers, mostly from Leiden.

Anyway, this shows that Murray N. Rothbard was right in revealing the fact that the state - how 'minimal' it might be - is an unnecesseray evil that will always encroach upon individual and civil liberties. (see also his splendid dissertation on http://www.mises.org/rothbard/newliberty01.asp , where he explains how the USA also turned into a statist hell. In fact, it already went wrong with Thomas Jefferson...)

Mr Peabody's Improbable History, or ...

Submitted by roughdoggo on Thu, 2007-07-12 23:11.

Butterfield Bettered.

My congratulations on a textbook example of the Whig interpretation of history!

( For those not in the flow, consult >en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whig_history< ).

I'm surprised, though, how you forgot to mention the Flemish invention of the incandescent lamp. In the twelfth century.

Anyhows, I'd like - with your permission, of course - to send this along to my friend, the reporter Mr B. Sagdiyev. May I?

@ Paul Belien

Submitted by USAntigoon on Thu, 2007-07-12 02:55.

Thanks for sharing.. Being a Flemish born, naturalized US citizen, I will start "telling stories" to my grandkids...

Whoda Thunk It ?

Submitted by Atlanticist911 on Wed, 2007-07-11 21:54.

So,it would appear that the U.S. Constitution isn't a poorly plagiarized version of the Iroquoise Constitution afterall.

http://www.campton.sau48.k12.nh.us/iroqconf.htm

And those words; cookie(koekje),dollar(daalder),and Santa Claus (SinterKlaus),all come from the Dutch,eh? I wonder,are we all absolutely sure that they are not derived from,say, the "Az(a)tlan" language,or even Classical Arabic?

Why,next I'll be reading somewhere that Ward Churchill isn't an "Honest Injun" !

http://www.nationalreview.com/flashback/miller200601271228.asp

Title: Honest Injun? by John J Miller

VH: Before the Magna Carta

Submitted by Brigands on Thu, 2006-02-23 16:40.

VH: Before the Magna Carta there was also the 'speech' of Iwein v Aalst to the Count of Flanders; in Ghent; 12th century IIRC; including notions of the people's sovereignty :)

Interesting

Submitted by Anonymous on Tue, 2005-07-12 21:21.

Not an article to comment a lot on. Very Barbara Tuchman-like. But you didn't mention the Magna Charta in England, as one of the other milestones in the limitation of the God-vested power of the King.

Of course, the concern in all this was not "democracy", it was money. In fact, the Flemish medieval towns and guilds are not that much the beginning of democracy, as well the beginning (and the success) of Capitalism. Royal French power in the 14-th century was cripled by the lack of money, as armies during the time consisted only out of hired professionals. And the Lombardian moneylenders really decided who would win a war.

Finally, the early "democracies" rather were a concern of the nobles against their taxing king than the common people's concern.

>>

Submitted by VHfc on Tue, 2005-07-12 21:23.

Forgot to log in before this comment.

VH

Ode to joyful entry

Submitted by Bob Doney on Mon, 2005-07-11 12:14.

From 1356 onwards every new Duke of Brabant, upon his accession, had to take a solemn vow, the so-called Joyful Entry. In this vow the prince promised to respect the liberties of the citizens and formally acknowledged that they had a right to rebel and “separate” from him if he did not do so.

As Anonymous says, an interesting article, and full of things I didn't know.

I especially like the Joyful Entry vow. Surely something like this for the incoming European Commissioners would be much more useful than the Treaty/Constitution. And much shorter.

And we could have a Hilarious Vow for European prime ministers and functionaries who still think the Constitution is alive and well and just in need of a little encouragement.

Bob Doney

I learn something new every day...

Submitted by Anonymous on Mon, 2005-07-11 02:10.

Thank you for the history lesson. I do not recall any of that about Manhatten from the American History classes that I attended. And since classes in World History were not required for my particular area of study, I did not know about any of this (the Carolingian empire, Charlemagne's grandsons, etc ). It was very interesting.

(This was my first visit here, I will come again.)